From Algorithms to Adventures

In my previous post, I shared the story of how I fell in love with maze algorithms. I wrote about porting Jamis Buck’s Ruby code to Swift, building a visualisation engine, and the intellectual joy of understanding “perfect” mazes.

I ended that project with a robust MazeGenerator framework and a technical demo. I felt like 90% of the work was done. I just needed to wrap some UI around it, add a “Start” button, and I’d have a game.

I was wrong. I had a simulation, not a game. And turning the former into the latter would take me on a journey through bad design decisions, harsh feedback, and a complete pivot in how I thought about “fun.”

The “Nerd” Trap (v1.0)

When you build a game engine before you build a game, you tend to value the wrong things. I was obsessed with the algorithms. I wanted players to appreciate the difference between the Recursive Backtracker (long, winding rivers) and Prim’s Algorithm (short, organic branches).

My first version of the game was essentially my tech demo with added controls.

- The Core Loop: Select an algorithm, generate a maze, solve it, and try not to touch any walls as you get points deducted for that.

- The “Cool” Feature: A “Draw Mode” where you could sketch a shape with your finger, and the framework would generate a maze around it.

- The Educational Angle: Info screens explaining “Diagonal Bias” and “Spanning Trees.”

I thought it was brilliant. It wasn’t. It was boring.

The Reality Check

You can’t convince people to use your app or play your game if you don’t do it yourself. I installed the game on my phone and tried to play it instead of Balatro or Mini Motorways. I didn’t last one hour. There wasn’t anything to keep me entertained or to make me want to win more points. I was bored.

Also, the “Draw Mode”? It turns out that drawing a mask with your fat finger on a phone screen results in a blocky, ugly shape. It was a technical marvel that resulted in a terrible user experience.

Finding the Fun

I was three months in. The codebase was sprawling with features nobody cared about (algorithm selectors, learning tabs, map editors). I had a choice to make: release a tech demo that no one would play, or strip back the nerdy features and make the game fun.

I chose the latter.

I stripped out the algorithm selector. I hid the educational content. I removed the Draw screen.

The Move Limit

The breakthrough came when I stopped punishing the player for hitting a wall and introduced a Move-Based system.

In the new version, you are given a strict budget of moves to solve the maze.

- Efficiency matters: You can’t just wander; you have to plan.

- Fairness is guaranteed: For any specific maze seed, the optimal path is a fixed number of steps. I could calculate the “Perfect Score” mathematically using Dijkstra’s algorithm.

- Tension: Running out of moves is far more stressful (in a good way) than a timer counting up.

Suddenly, it wasn’t a racing game anymore. It was a strategy game.

Building the “Game” Part

Once I had the core mechanic, I needed to wrap it in a progression system. A game needs to feel like a journey, not a loop.

I introduced:

- Power-ups: Since moves are vital to the game, power-ups became about economy. “Demolish Wall” costs coins to buy, but can help you get to that hidden crate and back before you run out of moves. “Jump” lets you skip long corridors and cash in on any remaining moves you have.

- Terrain: I added ice (you slide, saving moves but losing control) and mud (costs double moves).

- Progression: I added progressively harder levels - the mazes get bigger, the crates are further from the happy path, the terrain is rocky. Every ten levels, you get a prize. Every now and then, you unlock a rare avatar or stumble upon a hidden gem.

The Tech Stack: SwiftUI

I built the entire game in SwiftUI.

Many developers warned me against this, suggesting SpriteKit or Unity. But for a grid-based puzzle game, SwiftUI is surprisingly capable.

- State Management: The grid is composed of

VStacksandHStacks, rendered based on the game state. - Animations: SwiftUI’s implicit animations made the player movement (sliding from tile to tile) buttery smooth.

- Iterative Speed: I could change the “Mud” tile view in one file and see it update across the entire game instantly in the Preview.

The hardest part was positioning the “items” and the player layers on top of the maze layer. I ended up using a complex layering of ZStacks that I don’t recommend to the faint of heart, but it worked.

Launching

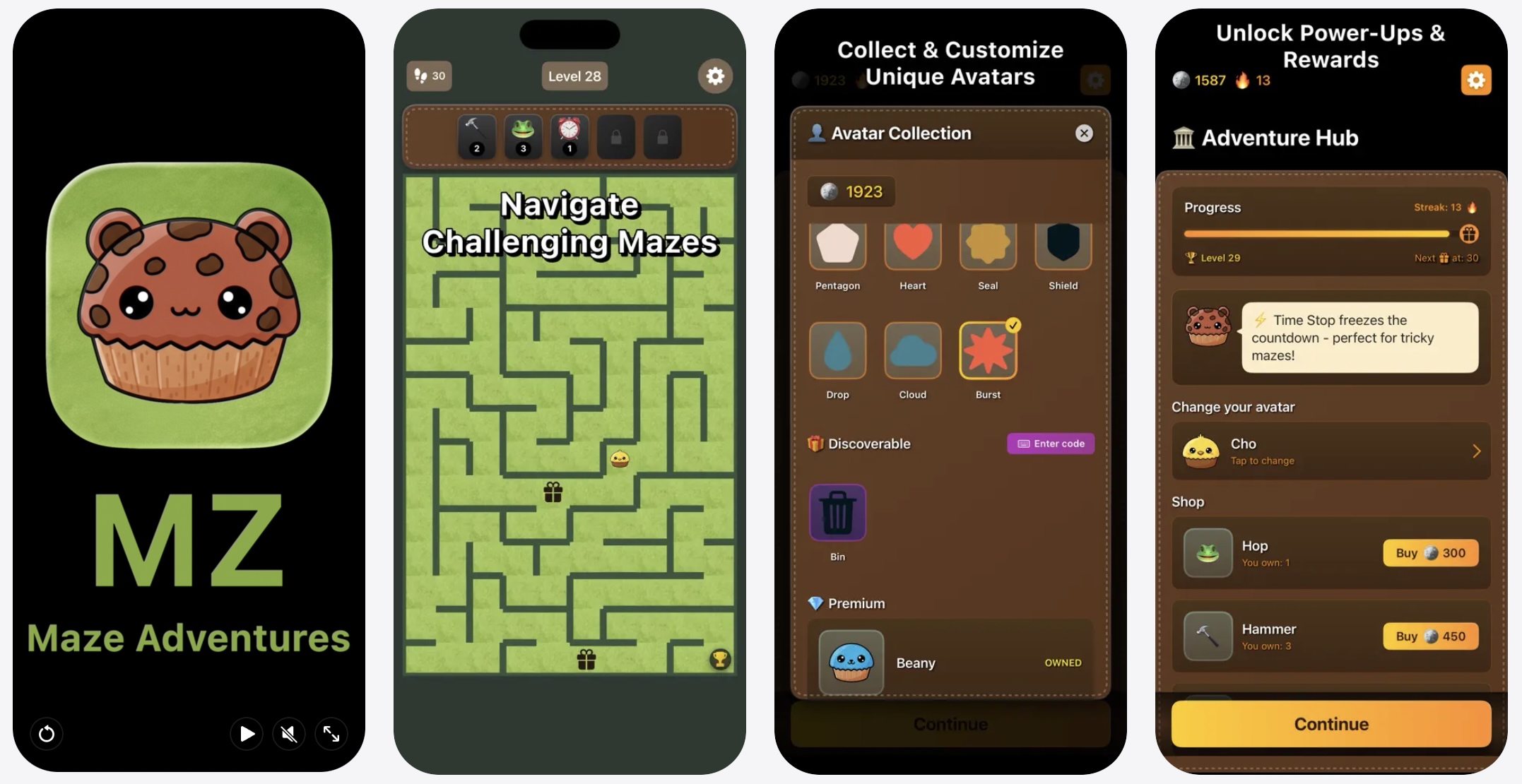

The game, MZ: Maze Adventures, is finished.

All the cute avatars in the game were designed by my wife; the not-so-cute ones - by me. The music was composed by my son (who also decided to download the game to play, not just to listen to his music in action). It has no algorithm selectors, no “Draw Mode,” and no educational lectures.

It just has mazes. Perfect, frustrating, beautiful mazes.

You can download it now on the App Store.